Grayson Perry: The MOST Specialest Relationship

On the eve of his Channel 4 series and as his new show opens, Claire Wrathall catches up with the ceramic artist who loves to court controversy.

Victoria Miro, London

15th September – 31st October 2020

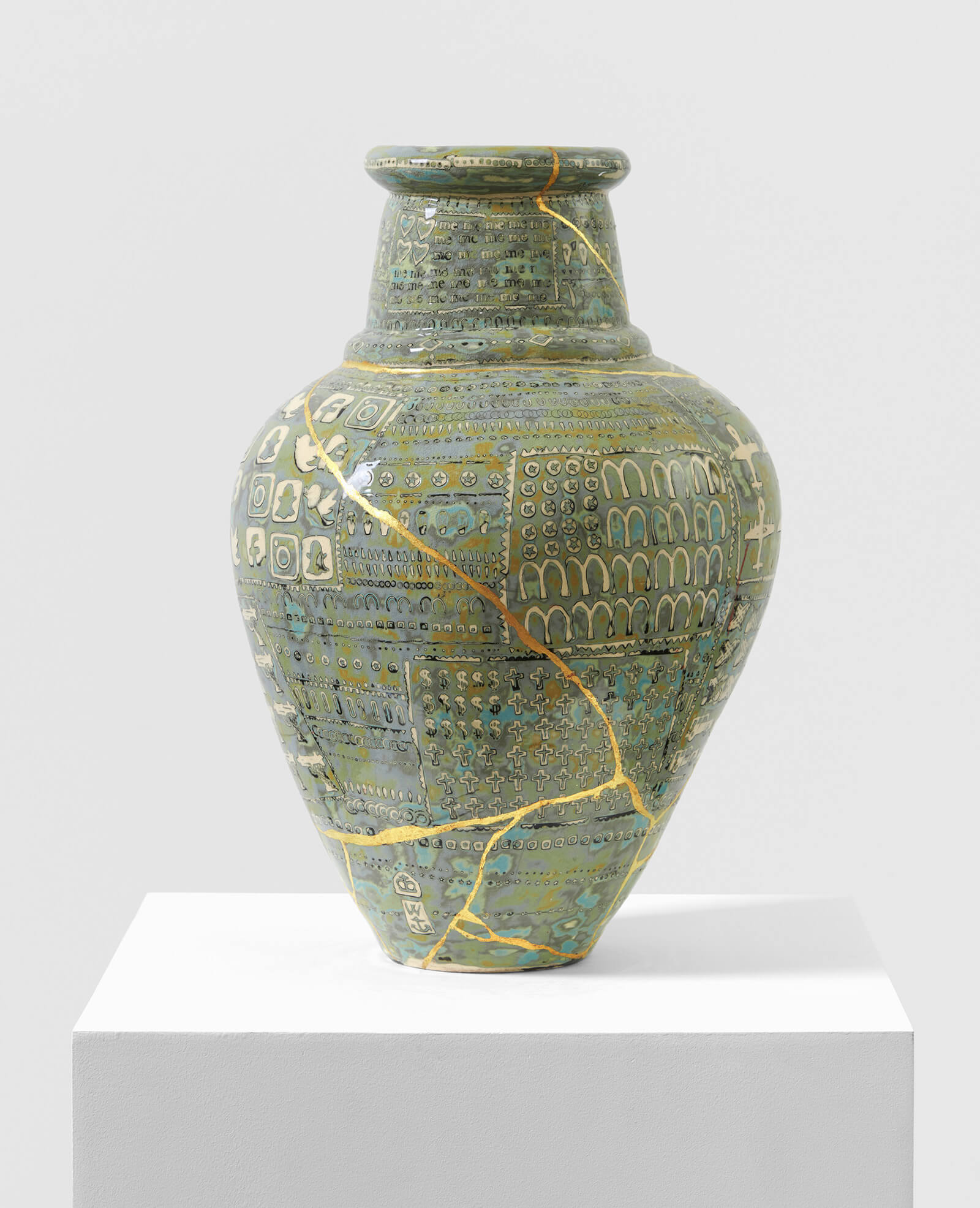

Grayson Perry, ‘Japanese, Korean and Persian Influence’, 2020

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro / © Grayson Perry

JUST BEFORE LONDON locked down last March, the Contemporary Art Society, which acquires works of art for public collections across the UK, held a fundraising dinner at Grayson Perry’s Islington studio. Towards the end of a (by-all-accounts) raucous evening, one of the hosts, the director of an eminent company of art handlers, got up to make a speech, knocking from a plinth a celadon-coloured vase inspired by ancient Islamic form, as he returned to his seat. The guests gasped as it smashed.

Of course, the “accident” was all part of the entertainment. Perry then took a hammer to it, destroying it further. But what might plausibly have been seen as a commentary on the themes of its decoration – a pattern evocative of the US flag where, in place of stars and stripes, there were serried arrangements of warplanes, cars, guns, McDonald’s Golden Arches, the Playboy bunny, and the Apple, Facebook and Twitter logos – was also part of the process. Perry sent fragments to his restorer, who pieced them back together, coating each break in golden lacquer in keeping with the Japanese art of Kintsugi, a tradition that seeks to make a virtue of breakage and rupture, venerating fragility and age by drawing attention to scars and fault lines rather than seeking to conceal them. The resulting pot, named ‘Japanese, Korean and Persian Influences’, is one of the 11 new ceramic works on show at Victoria Miro this autumn, alongside a huge tapestry and a map, all inspired by the “crass Americana” and deep cultural conflict he encountered on a road trip that took him from Atlanta to Martha’s Vineyard last year, the basis of a television series he has made for Channel 4.

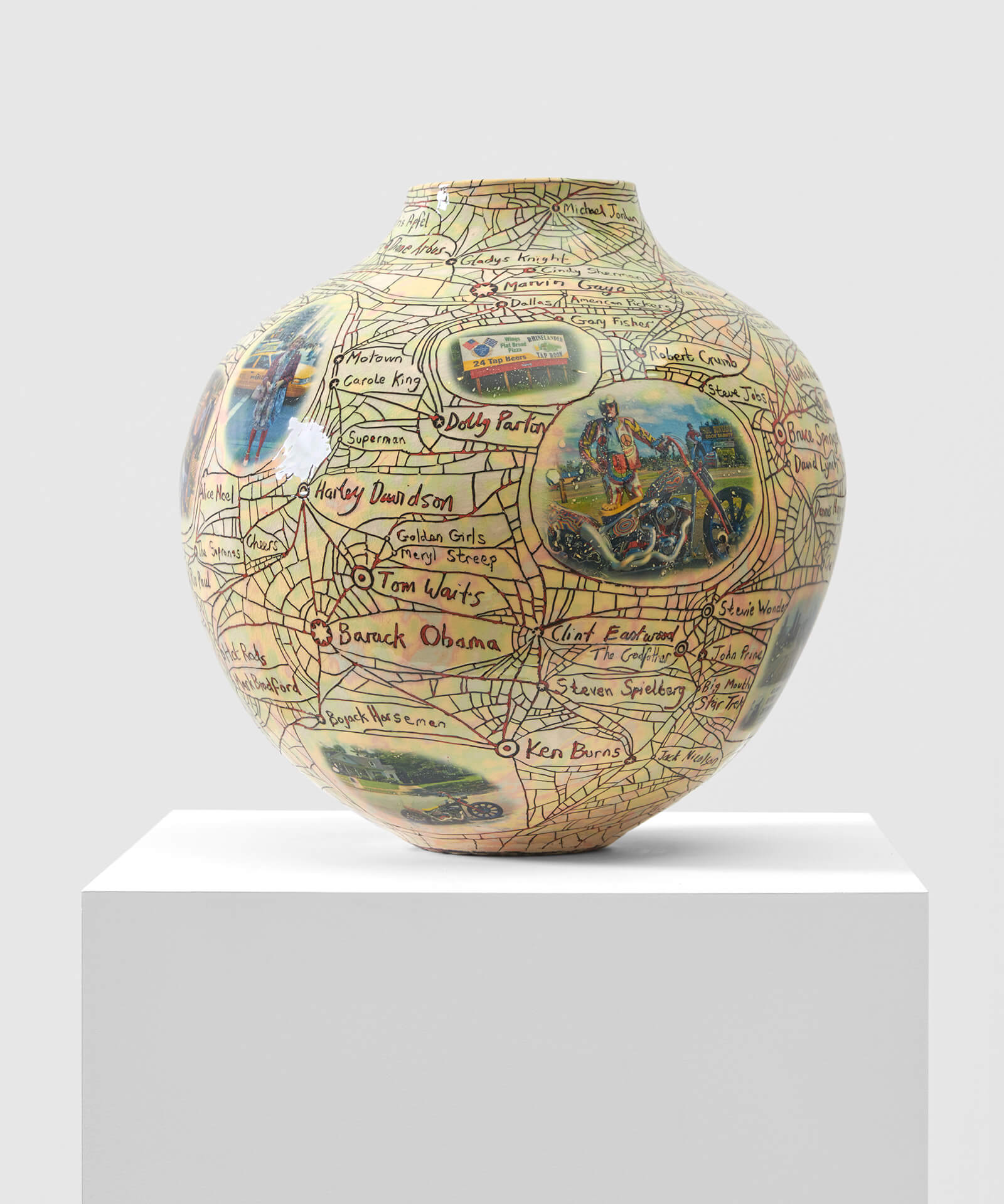

Grayson Perry, ‘American Journey’, 2020

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro / © Grayson Perry

The US may trouble him on many levels, but he “adores” its culture, he says. Hence, ‘American Journey’, a pot printed with photographs from the trip and inscribed with the names of numerous American cultural icons in acknowledgement of the contributions they’ve made to the world. They range “from hyperstars like Elvis and Walt Disney,” says Perry, “to forgotten heroes like Cliff Vaughs and Ben Hardy, who built the motorcycles ridden by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper in the film Easy Rider” – by way of Philip Roth, Stephen Sondheim and Donna Tartt.

That may be the sort of ceramic we’ve come to expect from Perry, but not everything here is a pot. There are six circular chargers, each more than half a metre wide, inspired by a piece of English press-moulded slipware, ‘St George and the Dragon’ by Samuel Malkin (1668-1741), he encountered at the Milwaukee Art Museum in Wisconsin.

Installation view

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro / © Grayson Perry

“I adore the simple relaxed drawing,” he says, noting that this “style of slipware was something that early settlers reproduced on American soil”. In ‘Vote Republican and Vote Republican Again’, he has drawn a horse similar to Malkin’s, though the saint has been supplanted by Donald Trump in a tricorn, surrounded by birds like the Twitter logo. The president appears on another plate as the crowned head of a farting lion with a forked tail, backed by the legend: “Republicans love art too.” Never afraid to bite the hand that feeds him, Perry is wise to the fact that not all collectors count themselves members of the liberal elite. “I like to make things that people want to put in their homes,” he says guilelessly. Beauty, decoration and heritage are important to him: even in the 17th century, English potters were using slipware as a medium for satire.

Grayson Perry

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro / © Grayson Perry

‘Aspects of My Sexuality and Gender Dressed Up as Colonial Settlers’, meanwhile, features two of Perry’s regular tropes: a goth version of his feminine alter ego, Claire, along with his teddy, Alan Measles, “togged out in 19th-century European clothes arriving in the ‘New World’ to find a piece of land and start of a new life.” A theme that is problematic on all sorts of levels, he says. “Aren’t crossdressers just perpetuating unhelpful gender stereotypes? [Today he is wearing a T-shirt and colourful dungarees, Mary Jane shoes and a quilted bonnet that might suit Little Bo Peep were it not embroidered with tiny penises.] Teddy bears are a sentimentalisation of a noble wild animal and surely using an image of a child’s toy in a work about gender and sexuality is tantamount to paedophilia. Colonial settlers were stealing land from Native Americans and they might have been slave owners. They established a Eurocentric class system that still flourishes in the US today. The very style of this artwork reinforces the conservative world view that holds back innovative young artists.”

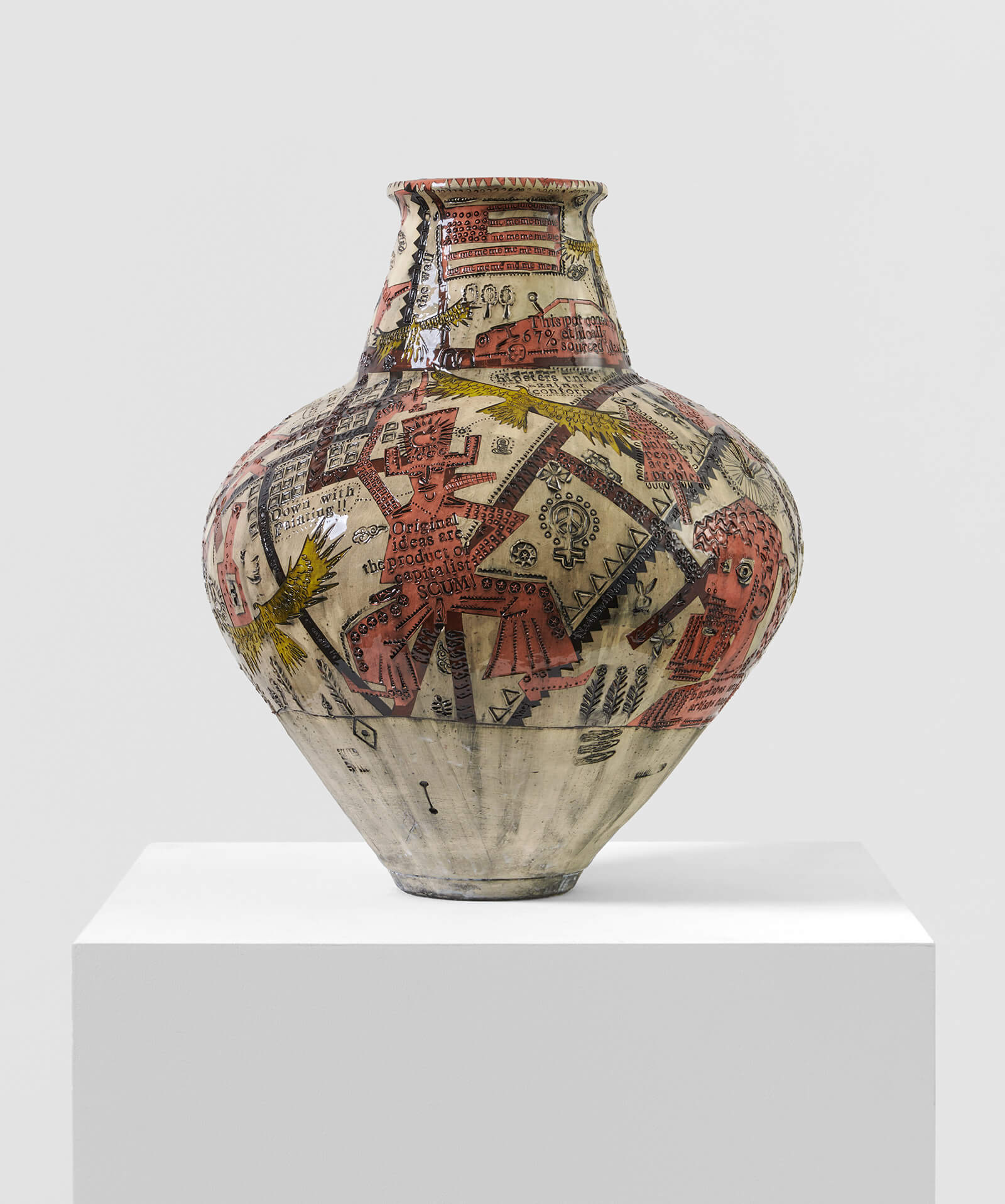

That it also seems to reference Grant Wood’s painting ‘American Gothic’, complete with carpenter’s gothic house in the background, was not, he insists, originally his intention. But he acknowledges the influence of other works he saw at the Art Institute of Chicago, notably his favourite work in the exhibition, ‘The Sacred Beliefs of the Liberal Elite’, which is based on a Native American pot, a fact he concedes “could be viewed as a gross act of cultural appropriation. But then drawing from different cultures has basically been my modus operandi for my entire career.”

Grayson Perry, ‘Sacred Beliefs of the Liberal Elite’, 2020

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro / © Grayson Perry

” Never afraid to bite the hand that feeds him …”

Grayson Perry, ‘Sacred Beliefs of the Liberal Elite’, 2020 (detail)

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro / © Grayson Perry

“… Perry is wise to the fact that not all collectors count themselves members of the liberal elite”

He’s courting controversy with ‘Warhead’ too, “a very literal transcription of an ancient Persian ceramic”, on which he has “faithfully replicated” a delicate network of white cracks. From a distance, the black torpedo-shaped motifs that adorn it would seem to be bombs. Look closer, however, and it transpires they are based on the horrifying diagrams of the British slave ship Brooks (published in 1788 by the politician, artist and abolitionist William Elford to raise awareness of the horrors of the slave trade). “Swimming up from depths of the mottled turquoise glaze are the distorted faces of Donald Trump,” reads the catalogue entry, which notes that the work was made before the killing of George Floyd last May and the Black Lives Matter protests it gave rise to.

So many timely issues in one vessel! Yet also the epitome of an “Insanely expensive decorative object for social justice”, one of the goading phrases on ‘Sacred Beliefs of the Liberal Elite?’ He pauses for a moment: “Everything is problematic if you dig deep enough.”

Grayson Perry: The MOST Specialest Relationship is at Victoria Miro, Wharf Road, London N1, until 31st October (by appointment).

Grayson Perry’s Big American Roadtrip begins on Channel 4 on 23rd September.