Fibre Art

Hanging, billowing or sculptural – textile and fibre artists are producing powerful works that defy categorisation.

Olga de Amaral, ‘Nébula 5’, 2015

COURTESY: Casa Amaral / PHOTOGRAPH: © Diego Amaral

CREATIONS MADE BY fibre and textile artists are gaining increasing visibility in the domain of collectible design. The Norwegian fibre artist Gjertrud Hals’s solo show at Galerie Maria Wettergren in Paris – now closed to visitors – featuring intricate, copper thread sculptures and mural pieces – exemplifies this burgeoning trend.

Gjertrud Hals, ‘EIR’ hanging sculpture group, 2019

COURTESY: Galerie Maria Wettergren

Hals’s three-dimensional, suspended works are characterised by undulating lines of copper wire “knitted” together with trailing stems. A couple of them have one oval form inside another and are imbued with an otherworldly, underwater quality. Standing in front of these captivating pieces, it’s perceptible how Hals’s early childhood memories of fishing nets have inspired her.

Installation view, ‘Sanctum’ by Gjertrud Hals at Galerie Maria Wettergren

COURTESY: Galerie Maria Wettergren

“We lived on an island where we were surrounded by fishing nets and in the summer we’d visit my grandparents on a very small island,” Hals reminisces. “Every evening, I’d go out with my grandfather in the boat to put out the fishing nets where they stayed overnight and every morning we’d go back out to see what fish, crabs and corals had been caught.”

Hals, 71, has been using fibres in her art ever since the 1970s. She was spurred on by how pioneering artists such as Sheila Hicks, Claire Zeisler and Magdalena Abakanowicz explored the sculptural potential of fibres in their practice.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, ‘Pregnant’, 1970-1980

COURTESY: Marlborough Fine Art / PHOTOGRAPH: Luke Walker

After making cubic pieces from fishing nets, she began working with cotton and linen threads, paper pulp, metals, crochet and lacework, gleaning ideas from Norse mythology and Shintoism, which she learned about whilst visiting Japanese temples. Anatomical books belonging to her neuropsychologist husband further stimulated her visual language and curiosity about “the many similarities between the roots of trees and the veins in our body”, she says.

Gjertrud Hals, ‘ERO Red’, 2019

COURTESY: Galerie Maria Wettergren

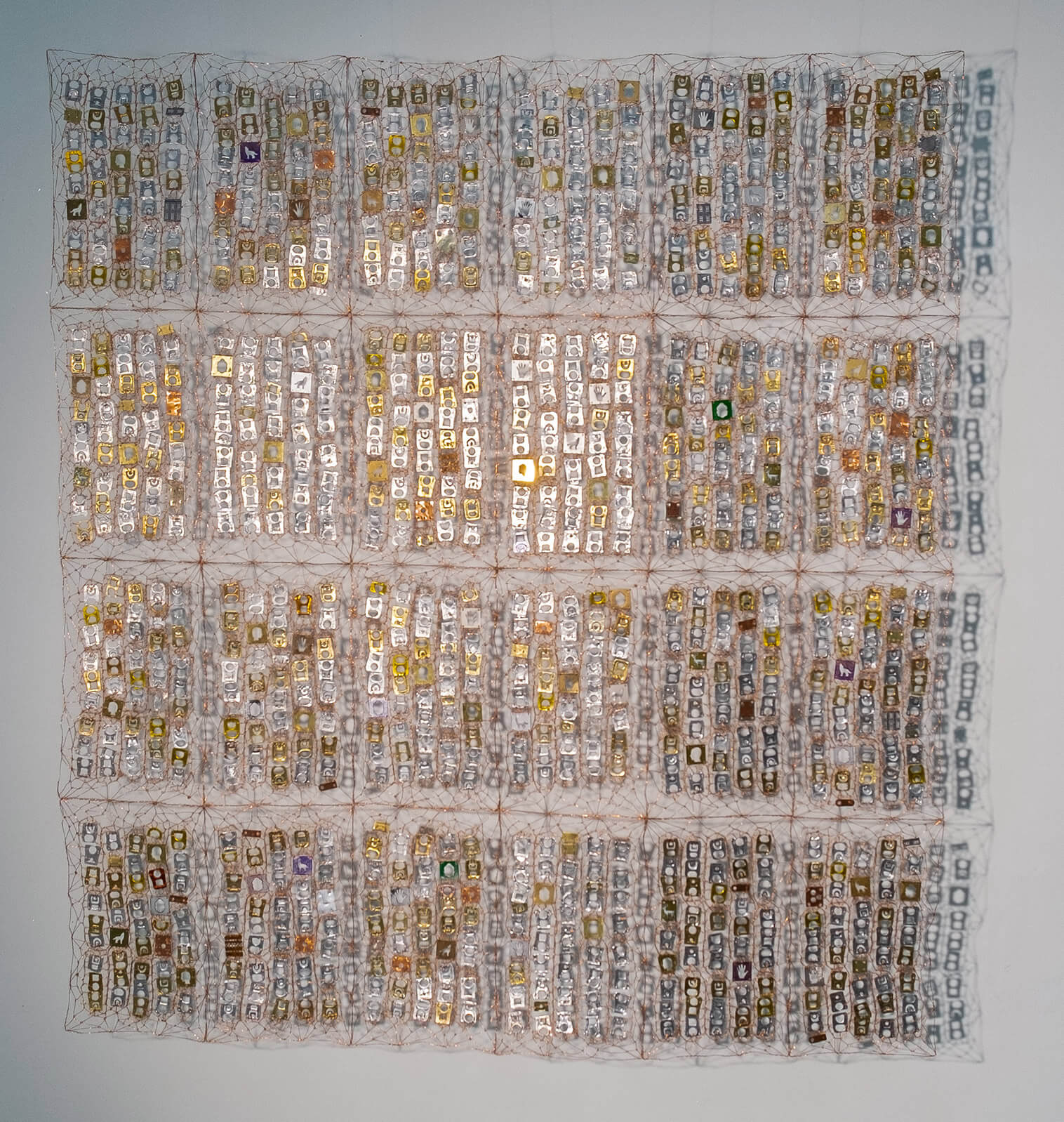

The first time Hals worked with knitted copper wire was for ‘Rekviem’ (2017), a memorial piece about her parents, recalling how her father was a metalworker and her mother loved to knit. This led to more two-dimensional, grid structures where small metal objects are interwoven like in a spider’s web. Bits and pieces from her father’s workshop, ring pulls from drink cans and laser-cut animals and leaves are elevated from the banal to the precious.

Gjertrud Hals, ‘Pilgrim Kirin’, 2020

COURTESY: Galerie Maria Wettergren

Hals’ work finds resonance with several other artists working today, from Hicks to Kiki Smith. “I went to see Kiki Smith’s exhibition at the Monnaie de Paris and she had many of the same ideas as me,” Hals says, referring to Smith’s take on nature, mythology and womanhood in her sculptures, tapestries and drawings.

Over in New York, Demisch Danant included wall sculptures by Hicks, 85, who had a retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2018, in its recent ‘Color Diaries’ exhibition. Similarly, the fabulous, shimmering textile works, made with linen, gold, paper and gesso, by the Colombian artist Olga de Amaral, 87, have been presented at the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris. Amaral was recognised as an Artist Visionary by the Museum of Art and Design (MAD) in New York in 2005.

Olga de Amaral, ‘Entre Ríos 7’, 2012

COURTESY: Casa Amaral / PHOTOGRAPH: © Diego Amaral

“What seduces collectors is the unarguable sincerity with which Olga de Amaral treats her sources, from the Inca’s use of gold to the Amazon’s indigenous peoples using raw textile fibres and brilliant pigments,” Constantin Chariot, managing director of La Patinoire Royale – Galerie Valérie Bach in Brussels, says. “She revitalises her country’s artistic and ethnographic heritage with sensitivity and inventiveness, creating work respectful of ancestral traditions that is also at the meeting point of art and craftsmanship.”

Olga de Amaral, ‘Nudo 16’, 2014

COURTESY: Casa Amaral / PHOTOGRAPH: © Diego Amaral

Indeed, fibre and textile works often find themselves at the intersection of art, craftsmanship and decorative arts. For instance, Norway’s Hanne Friis has exhibited at QB Gallery – a contemporary art gallery in Oslo – and at Galerie Maria Wettergren’s stands at PAD and TEFAF. She is participating in the group show, ‘Nice to (finally) meet you!’, exploring the boundaries of material, at the Seinäjoki Kunsthalle in Finland.

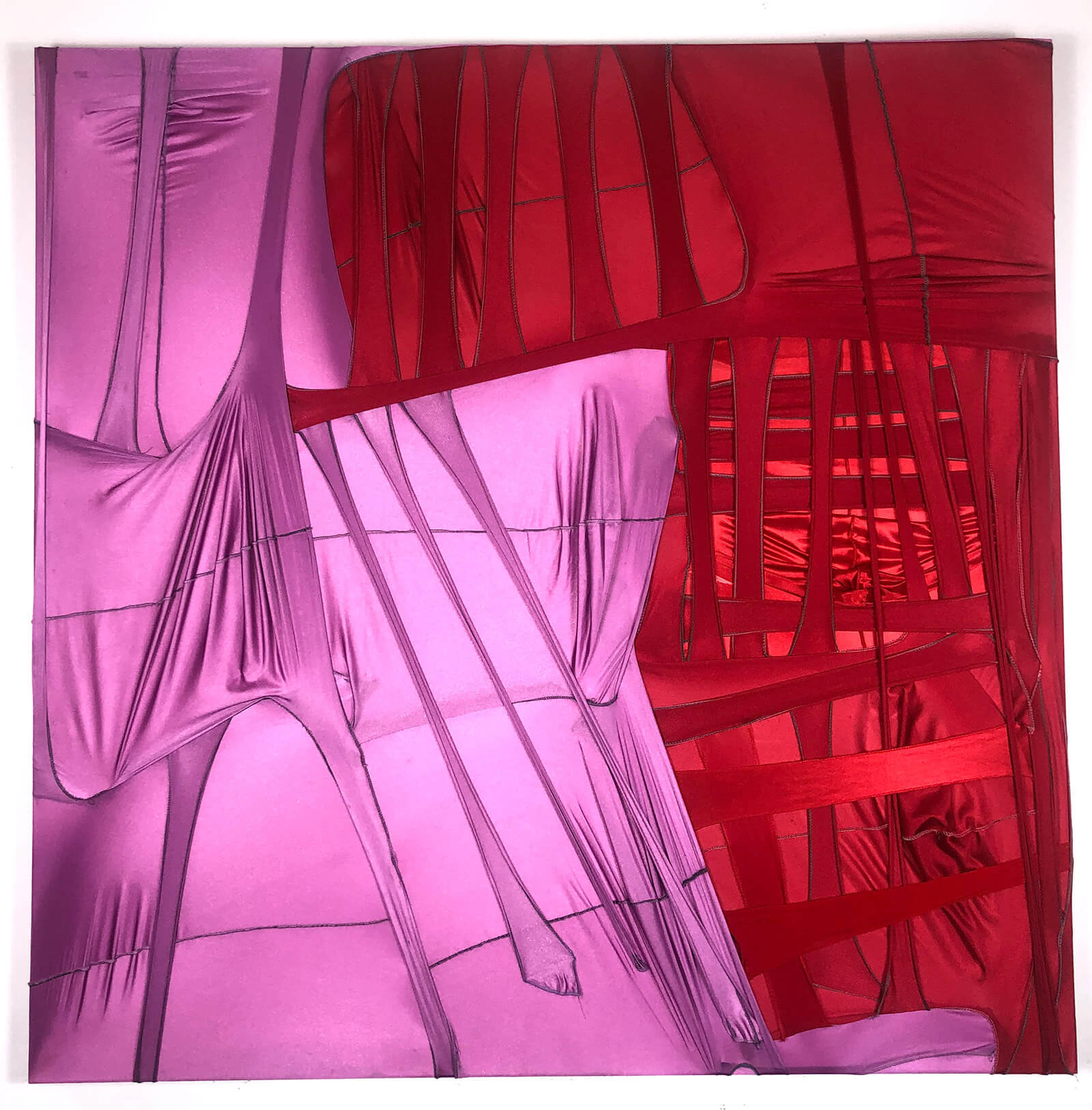

Hanne Friis, ‘Topography I’, 2019

COURTESY: Hanne Friis / PHOTOGRAPH: Øystein Thorvaldsen

Friis has been making textile sculptures, which she elaborately pleats, sews and hand-stitches using “many metres of fabric”, for around two decades. “It’s quite a long process but I sit on the floor to do the sewing and little by little the shapes develop,” Friis says. She uses sketches to guide her and hand-dyes the material with organic pigments obtained from lichen, mushrooms, acorns and other plants. As she explains, “I collect the plants and soak the material in the dye as you get beautiful, nuanced colours from nature, and some of the processes can take many days.”

The abstract forms that develop can resemble a waterfall or swollen, organic matter, often encompassing a sense of growth, movement and vulnerability. This renders Friis’s work simultaneously sensual yet disquieting. “Some pieces can be a little frightening, like the uncontrollable growth of cancer, or how things are changing due to climate change and how the body changes,” she says.

Hanne Friis, ‘Grey Spiral’, 2018

COURTESY: Hanne Friis / PHOTOGRAPH: Øystein Thorvaldsen

After doing embroidery and knitting as a child, Friis, 47, became interested in the tactility of textiles after admiring how Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois used textiles in their sculptures. “Now you see a lot of textile art in galleries but in the 1990s a lot of art was conceptual so I also sought inspiration from other disciplines than in the art world,” says Friis, who is working on a large commission, partly inspired by corals, for a boat.

“Her textile works are highly original visually and are a kind of craftsmanship that collectors are starting to value,” Mikaela Bruhn Aschim, director of QB Gallery, says. “There’s very much a wave of textile artists being recognised for their work over the last decade and a lot of collectors now know that they should include textile works in their collections.”

The diversity of artists using fibres takes in Cecilie Bendixen’s meticulous, monochromatic works, Astrid Krogh’s sculptures combining optic fibres and light monitors, and Jacob Hashimoto’s wall sculptures and installations, made by painstakingly threading dozens of tiny, hand painted, kite-like elements together. Hashimoto’s work, which reveals an influence of Japanese landscape painting, was exhibited earlier this year at Galerie Italienne in Paris. Another example is the Campana brothers, whose ‘Sushi Mirror – Pendant 1’ (2012), is constructed from aluminium and stainless steel mirrors, bordered by curling waves made from carpet, fabrics and rubber.

Jacob Hashimoto, ‘All Looped Around in this Finite Forest of Past Future’s History’, 2019

COURTESY: Jacob Hashimoto / PHOTOGRAPH: © Michele Alberto Sereni

While it is often women that are most associated with fibre and textile art, male practitioners have been entering this domain, too. Joël Andrianomearisoa, who represented Madagascar at the Venice Biennale last year, makes site-specific installations and smaller pieces using multilayered, repetitive squares of black fabric, creating a nocturnal ambience. Meanwhile, Anthony Akinbola, an American artist of Nigerian origin, makes multilayered compositions known as ‘durag paintings’ from headscarves customarily worn by women of African origin to protect their hair. Akinbola, 28, was an artist fellow at MAD last year, where his installation ‘Local Import’, made by sewing dozens of durags together, was exhibited in the sixth-floor project space. Highly political as well as aesthetically striking, his work engages issues of identity and commodification of African-American culture.

Anthony Akinbola, ‘Camouflage #14 (Valentino)’, 2020

COURTESY: Slag Gallery, NewYork

“Anthony Akinbola invites us to engage with his work, whether or not you immediately recognise the materials he has repurposed for making art,” April Kim Tonin, MAD’s deputy director of education, says. “Visitors of all ages were inspired to see the durags take centre stage in his work because of a shared cultural experience and pride. For other viewers, they understood on a personal level the dual identity of someone like Akinbola, an artist of the diaspora, who moves between cultures.”

Textiles also take centre stage in Ulla von Brandenburg’s exhibition, ‘Le milieu est bleu’, at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. Fabrics from the German artist’s previous installations are used as backdrops and perspectives in a fictional, performative narrative about a nomadic community that has left a theatre and settled in the art institution.

Ulla von Brandenburg, ‘Das Was 1st’, 2020

COURTESY: Ulla von Brandenburg / PHOTOGRAPH: Aurélien Mole

“I’ve been working with fabrics ever since I was an artist,” von Brandenburg says. “For me, textiles are the material that are the closest to the body – when we’re born, we are put in fabric right away and when we die, we are enveloped in fabric. It’s the material that takes the most imprints or information of people and is also the most flexible.” This communal aspect of fibres and textiles, within the context of craftsmanship and art, carries political weight in her work.

Ulla von Brandenburg, ‘Das Was 1st’, 2020

COURTESY: Ulla von Brandenburg / PHOTOGRAPH: Aurélien Mole

Certainly, as more artists embrace fibres and textiles in interdisciplinary, multitudinous ways, there is plenty of opportunity for curious collectors eager to broaden their collection.

‘Gjertrud Hals: Sanctum’ is at Galerie Maria Wettergren, Paris, until 25th April 2020.

‘Nice to (finally) meet you!’, featuring Hanne Friis, Sigurdur Gudjónsson and Julie Stavad, is at Seinäjoki Kunsthalle, Finland, until 1st August 2020.

‘Ulla von Brandenburg: Le milieu est bleu’ is at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, until 17th May 2020.

Currently all closed, check with the institutions directly to see when they may reopen.