Achille Salvagni / architect and designer

On the eve of the publication of his monograph, Claire Wrathall meets the man who explores myths with his furniture.

Achille Salvagni with Gianni Piacentino’s ‘Purple-Gray Window Object’, 1967-1968

PHOTOGRAPH: Serenda Laudisa

Look at an object or a piece of furniture by Achille Salvagni, and its design will as often as not be informed by a story. The credenza ‘Antinoo’, for instance, which he created in an edition of six in 2014, is named after Antinous, lover of the first-century Roman emperor Hadrian, and the subject of Marguerite Yourcenar’s 1951 novel Memoirs of Hadrian. It tells the story of Hadrian’s seven-year relationship with the beautiful youth, whom he kept a virtual prisoner lest someone else fall in love with him. Salvagni loved the book and was captivated by the idea of a figure who could, as he puts it, “see out into the world, but not join it.”

Achille Salvagni, ‘Antinoo Parchment’, 2014

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Look at the panel of gilded bronze that runs between its convex oak doors (their almost mirror-finish the result of many coats of burnished shellac, a process that can take two months), and there within their embrace, as Salvagni sees it, two eyes and an elongated nose reminiscent of a Cycladic head, or the nose-protector on a Roman helmet, have been inscribed, thus elevating a piece of furniture to a work of art.

“I find it slightly sad,” he told me – not an adjective one would ordinarily use of a sideboard – urging me to “look at the legs”, the backs of which are, like the panel and the hinges, plated in 24ct gold. “See their angle. They are not vertical but inclined,” splayed outwards to suggest the legs-apart stance of a man of authority. “I could create portraits with my furniture,” he continues. “I’m interested in more than just shapes. I need something more. I prefer to create pieces that embody or evoke a story.”

Achille Salvagni, ‘Lancea’, 2017

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Salvagni finds inspiration in the most eclectic places. The farthingale skirt worn by Elizabeth I in the Ditchley portrait in London’s National Portrait Gallery became the basis for the ribbed silk shade on his ‘Lancea’ lamp. A trip to a milonga in Buenos Aires gave him the idea for the console ‘Tango’ (again, look at the angles of its legs).

Achille Salvagni, Tango Parchment’, 2015

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

The plump armchairs ‘Gae’ and ‘Vittoria’ were informed by the soft limbs of his own children when they were babies.

Achille Salvagni, ‘Gae’, 2017

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Achille Salvagni, ‘Vittoria’, 2015

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Even Jeff Koons’s balloon sculptures have played their part, giving rise to his ‘Bubbles’ table lamp, four spheres of onyx, each lit from within by an LED, and three globes gold-plated bronze set on a block of black granite, which Koons himself commissioned.

Achille Salvagni, ‘Bubbles’, 2013

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

But mythology remains an enduring wellspring of ideas. Take his latest collection, ‘Laguna’, its name a reference to the Venetian lagoon and the Murano glass it incorporates. This has been fabricated from a supply of silica ground in the 1920s or 30s, that a glassblower Salvagni knows happened upon by chance. Over the ensuing century, its colours – a strong pink, a deep blue, an acid green and a black that “diffuses a sense of burgundy” – had aged and altered, making the resulting shades extremely rare and unusual and giving it, Salvagni says, “the allure, the feeling of something from 100 years ago, but not of course the same shape.”

Aldus (Achille Salvagni and Fabio Gnessi), ‘Medusa’, 2019. From the ‘Laguna’ collection.

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

The collection embraces three reworkings of his already classic three-legged side table ‘Drop’, this time with a top of blown glass; a new version of his ‘Spider’ chandelier hung with stalactite-like droplets of glass; and the reinvention of his ‘Venezia’ sconces.

Achille Salvagni, ‘Drop Ebony’, 2015

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Achille Salvagni, ‘Spider Laguna’, 2019. From the ‘Laguna’ collection.

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

But the centrepiece of the collection is a bar cabinet, ‘Dido’ (still in production as The Design Edit went to press), named after the Phoenician queen who founded Carthage in the ninth century BC, in which the stretched pale pink parchment that covers its doors is encrusted with pieces of black glass, a material favoured by the Phoenicians and symbolic of her suffering. As he explains, “She fell in love with Aeneas, and when he left to conquer Italy, leaving her alone, she committed suicide with his sword.” The handle, he adds, is engraved with their faces.

Aldus (Achille Salvagni and Fabio Gnessi), ‘Oceano’, 2019. From the ‘Laguna’ collection.

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Then there are three mouth-blown glass vessels, ‘Oceano’, ‘Poseidone’ and ‘Tritone’, after three mythological Greek sea gods, that are almost fluid in form.

Aldus (Achille Salvagni and Fabio Gnessi), ‘Poseidone’, 2019. From the ‘Laguna’ collection.

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

The idea was “to recreate clear organic shapes with the sense of a bubbles rising,” he says, but also to evoke fire: hence their removable flame-shaped finials, which means they can double as vases and candleholders.

Aldus (Achille Salvagni and Fabio Gnessi), ‘Tritone’, 2019. From the ‘Laguna’ collection.

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Salvagni has been drawing since childhood and always liked making things. For his eighth birthday, his parents gave him a workbench with a vice. “My mother says I kept a hammer and a screwdriver under my pillow at night,” he recalls in the first monograph on his work, which is also published this autumn.

Front cover of Achille Salvagni by Pilar Viladas, published by Rizzoli New York, 2019

COURTESY: © Achille Salvagni

His father worked in construction, and as a child he would accompany him on site visits, instilling in him both a love of materials and an understanding of design and all the crafts involved. So perhaps he was destined to train as an architect, first in his native Rome, then in Stockholm, where he went “to refresh my mind and get rid of all the imperial, Renaissance and baroque history,” that he felt was dominating his thinking.

The trouble with studying in Rome, he says, is that “whenever you try to move towards rationalism, in through the window jumps Classicism.” Witness a skylight he designed for the superyacht ‘Aurora’ based on the oval dome of Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. “So going to Sweden was a way for me to cool down and to learn to think internationally.” He also discovered the work of designers such as Alvar Aalto, Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz; though if he had to single out an overarching influence, he’d name Gio Ponti. “He was many things: a designer, a tastemaker, a collector … His work embraced a wide range of sophisticated ‘experiments’ in everything from cutlery to urban masterplanning.”

Achille Salvagni, skylight from the superyacht Aurora

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

Salvagni returned to Rome and joined an architectural practice before establishing his own studio in 2002, where his big break came when a client for whom he had worked on a chain of supermarkets asked him to design the interior of a yacht. (If he had been “too picky” starting out, he notes pragmatically, “I wouldn’t have survived.”)

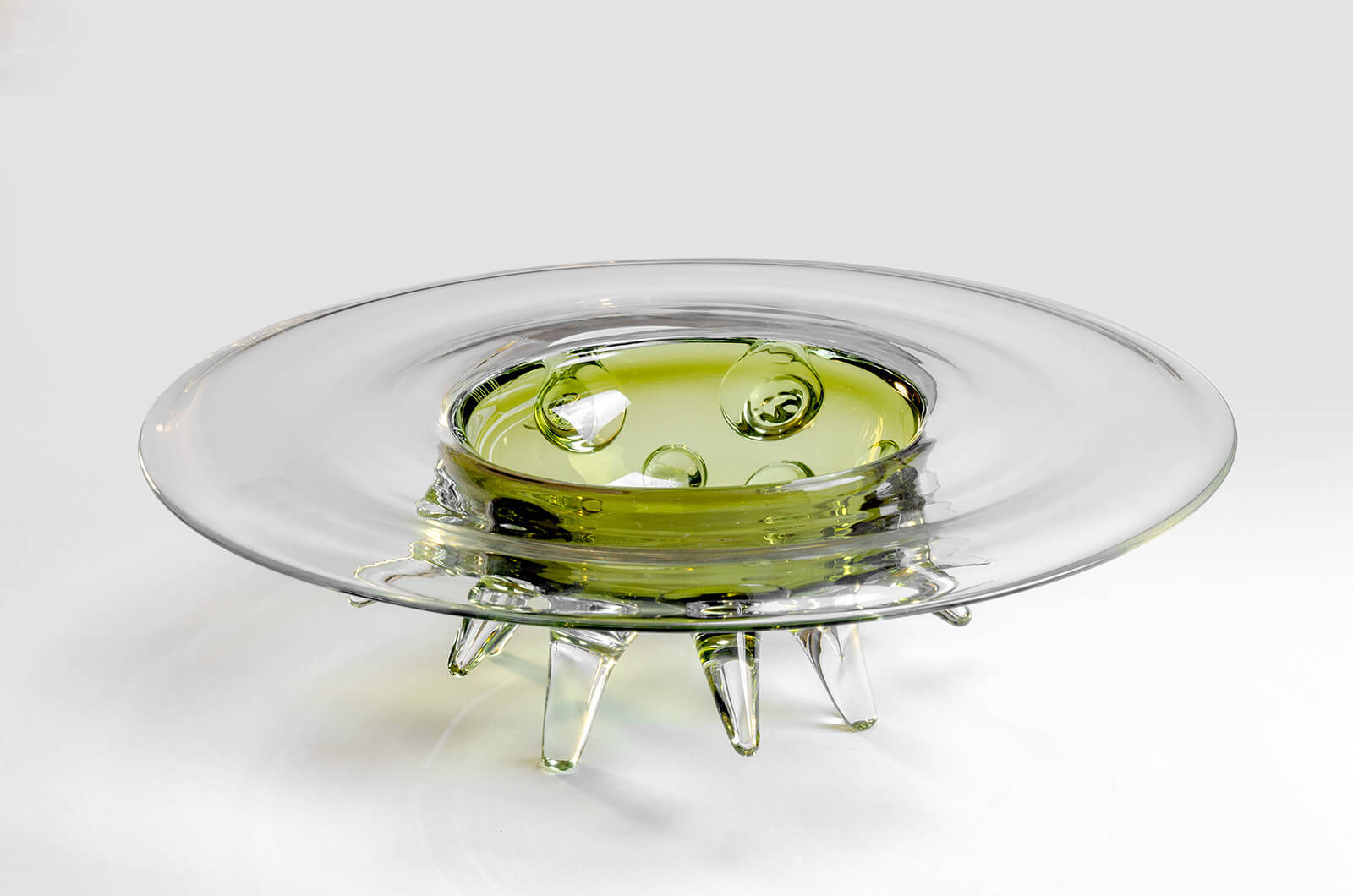

Aldus (Achille Salvagni and Fabio Gnessi), ‘Chimera’, 2019. From the ‘Laguna’ collection.

PHOTOGRAPH: Achille Salvagni atelier

It proved a turning point: “Big furniture doesn’t work on yachts, so I started to design my own,” he said. This conditioned him to think seriously about both dimensions and materials, not least about how those used in the fabrication of individual pieces of furniture might be deployed in the decoration of walls. Witness the use of subtly reflective alpaca panelling in his London gallery, a silvery alloy of copper, nickel and zinc that reminds him of old Venetian mirrors. In contrast the opposite walls are lined in brushed stained oak inset with narrow panels of gilded brass, with intriguing textured finishes. “We didn’t have any tools to hand when we were making these,” he says, “so we used pasta – spaghetti, rigatoni, fusilli, stellini – just rolled over, or pressed into the clay, to make the moulds.”

For just as Salvagni likes to play with narratives, so he strives to marry opposites: light with dark; rough with shiny; past with present; craft with technology. In essence, “I want to evoke the allure and the quality of the past,” he says, “while at the same time looking to the future.”

‘Achille Salvagni’, a film by Freddie Leyden

COURTESY: Achille Salvagni Atelier

Achille Salvagni Atelier – a collection of unique objects and bespoke furniture. Exclusive interior design and limited edition furniture, mirrors, lighting and seating.

‘Laguna’ will be on show at PAD London, 30th September – 6th October.

‘Achille Salvagni’ by Pilar Viladas, is published by Rizzoli on 24th September, £50.