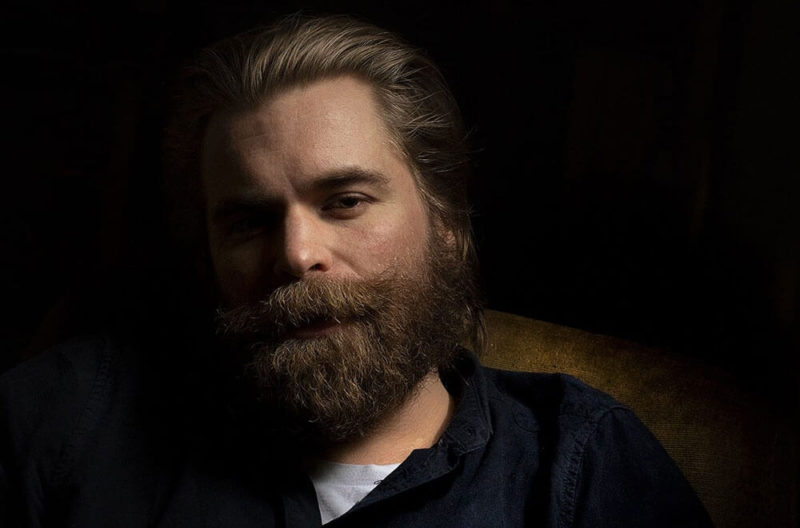

Rashmi Bidasaria

Royal College of Art

Rashmi Bidasaria

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

BEFORE BEGINNING HER masters at the Royal College of Art in 2018, Bidasaria was studying and working as an architect in India. There, she worked closely with designer Sandeep Sangaru, who taught her the value of bringing the community into her practice. Bidasaria has since adopted a collaborative approach to her work, seeking to engage with and promote the worker. This is a theme that runs through Bidasaria’s work and is embedded into all her designs. The raw finish of ‘Dross’, in particular, is a nod towards the steelworkers who were so integral to the project’s creation and around whom it was designed.

In 2019, Bidasaria was awarded the Textile Museum Scholarship to fund the project, ‘Kaarigari’. 2020 was busier still, as Bidasaria was invited to speak as a panellist at ‘Waste to Wealth Conference by Steel and Metallurgy’ and was shortlisted for the Lexus Design Awards for her graduate project, ‘Dross’.

Rashmi Bidasaria, ‘Dross’ Monolith Low Table, 2020

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

The Design Edit (TDE): Tell us about the inspiration behind your graduate project, ‘Dross’?

Rashmi Bidasaria: I wouldn’t say it was inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic, but the way the project developed was definitely shaped by it. Last March, I was forced to drop everything in London and come back to my hometown in Hubli, here in southern India, to be with my family.

My grandmother piping out Mangodi (lentil paste, a traditional Indian condiment). The joy in keeping up cultural-handmade traditions.

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

I chose to continue my Masters program remotely and because of the way I work, I needed to start making something straight away – but I didn’t have any access to any materials or workshops because of the lockdown. I realised that the local steelworks, Southern Ferro Ltd. Hubli, had lots of raw materials and machinery, everything I needed. But I also thought a lot about the waste that the factory produces, which is expensive to dispose of. So I looked into ways to turn that expense into revenue. And because all I had was the factory, I had to use what I had ready access to – the waste products, the things all around us that were just discarded or cast away. I used steel slag and quartz, residual heat, and the knowledge that the workers already had from their craft. It became a very utilitarian process.

Steel factory, India, ‘Dross – Rest Away Table’, May 2020 – reminding me that ‘breaking’ points are important

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

A lot of Indian factories provide living arrangements in the factory, so I had envisioned that the ‘Dross’ pieces would be used in the communal spaces. In the making of ‘Dross’, I replicated the industrial processes that the workers were familiar with, which meant they could easily fix or replace the furniture. Also, the material is free, in the sense that it is waste and is just lying around, so there is no expense to the workers. This helps them to be more self-sufficient and gives them more agency.

Steelworker eating off ‘Dross’ Floor Table

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

TDE: Where are you going to take that work now?

Rashmi Bidasaria: It’s very exciting, this question. I’ve had to think about it a lot recently, as coming out of art school you lose all your scaffolding and you’re just launched out into the world.

I feel like there is a lot to work on with the material itself. It was developed in a context where it could be easily fixed or replaced by the workers. But I want to make it more durable and better suited for domestic use. So I’ve been trying to bridge it into the market whilst keeping the rich history of the material evident in the design. I want the customer to understand the project, the process, the energy and the effort that’s gone into it.

I’m in the early stages of experimenting with ceramic glazes because I noticed similarities in the way ‘Dross’ is made. But I’m just excited to see how it’s progressing and to bring it into the market and see where it goes.

Rashmi Bidasaria with ‘Dross’ Rest Away Table and Bench, 2020

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

TDE: Which designer is your role model or most inspires you?

Rashmi Bidasaria: I have a different role model for each discipline. But I mentioned Sandeep Sangaru, as he influenced me a lot when I had the opportunity to work with him for six months. He’s changed a lot in my life, the way I think about design and the way that I approach my work. Alongside Sandeep Sangaru, I had a chance to work with Sarah and Tim from Studio Glithero, London in 2019. These three designers have taught me how to get to know the material itself, focus on the process and allow that learning to guide my design principles.

I would also mention Stefanie Posavec and Giorgia Lupi, two designers who work with data visualisation. They’ve inspired me a lot because of their own relationship with each other – and as designers because of the kind of information they bring to the world. Their book Dear Data has been very influential in my life, particularly on another of my works, ‘Kaarigari’.

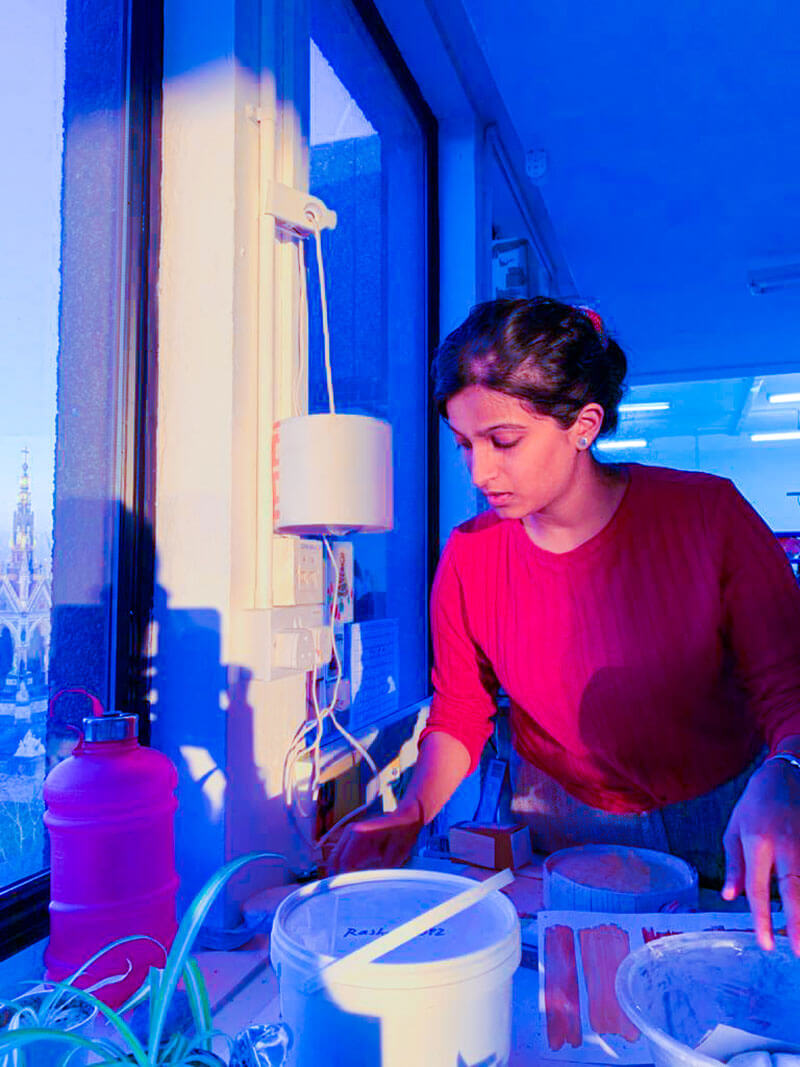

Caught in the act/ Golden Hour/ Pop of colours, Royal College of Art London, Darwin Building 8th Floor Studio

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

TDE: What is your standout memory from 2020?

Rashmi Bidasaria: I was invited by a steel industrialist to speak about ‘Dross’ at a steel conference. It was completely out of the blue, I didn’t know what to expect. It was interesting for me because all the people at the conference were policymakers, businessmen or manufacturers and they had little or no idea about design, but were very interested.

On the day of the conference I realised I was the only woman on that entire call – both on the panel of 50 and the audience of around 1,000. I felt proud, of course, because it felt like I was paving a way into a male-dominated industry. From a personal perspective, it was encouraging to be invited to talk about my work, receive feedback and build on that conversation because I’ve always tried to work with people on a project to bring the community together. At that moment it felt as though that aspect of my practice had become a reality. I could really imagine working to bring these parts of society together for the rest of my life.

TDE: What was the most important thing you learned at your design college?

Rashmi Bidasaria: The value of my peers, of the knowledge they have, just learning from everybody in the studio. Not just by having conversations, but also by looking at the way somebody organises their desk and the mistakes they make.

“My mess and my process (Mental & Literal)”, Royal College of Art London, Darwin Building 8th Floor Studio

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

One of my favourite memories from school was the first day. We were asked to design our own studio desks so they gave us a very basic shell and told us to do whatever we liked. So people started pulling out toolboxes and it suddenly occurred to me, oh my god … I don’t know how to do this! While working as an architect in India I’d had a minimal hands-on practice, so I didn’t even know how to use a hand drill! So my friend says, “What’s wrong with you? You’re a certified architect, and you don’t know how to drill a hole in the wall?” He was very patient and taught me to do it right. It was so embarrassing, but it was an important and memorable lesson for me. I love that memory of us!

Everybody in the studio knew everything about something. If you wanted something you just had to shout out, “Does anybody know this, that or the other?” It was as simple as that. It was like working in a living, breathing library. So just being able to have these conversations and to learn from them was really interesting for me.

TDE: What is your song of 2020?

RB: If I could slightly cheat with this question, I’d say it’s a song podcast – Above & Beyond Group Therapy. They do a two-hour long set bringing music from all around the world and hosting it live every Friday. It gave me a sense of connectedness at a time when we all needed it the most.

Rashmi Bidasaria: ‘Dross’ 2020

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

Rashmi Bidasaria: ‘Dross’ 2020

COURTESY: Rashmi Bidasaria

THE DESIGN EDIT