Pioneering Women

An exhibition that highlights the diversity, strength and influence of three generations of female ceramists.

Oxford Ceramics Gallery

14th February – 27th March 2021

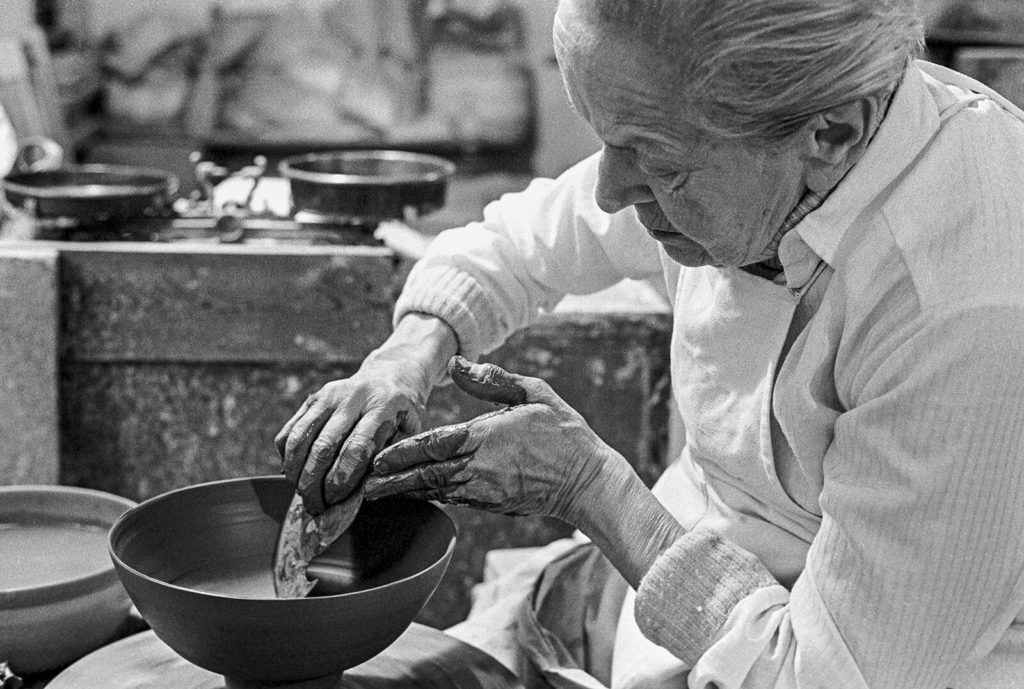

Lucie Rie, 1983

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: © Ben Boswell

IT WAS A genuinely jaw-dropping moment. On 19th November at MAAK’s Modern + Contemporary Ceramics auction a pot entitled ‘Angled Mixed Coloured Piece’ by Magdalene Odundo sold for the astonishing price of £240,000 – the world record at auction for a single vessel by a living ceramist. “We knew we had something special,” MAAK’s founder Marijke Varrall-Jones tells me over Zoom. “We knew it deserved to do really well but I don’t think anyone anticipated it getting to that level. I’ll be honest with you, my view was if we made £60-80,000 on it that would be really respectable.”

Magdalene Odundo, ‘Angled Mixed Coloured Piece’, 1988

COURTESY: MAAK

The Kenyan-born, Surrey-based artist wasn’t the only female potter to do well that day. Mary Rogers’ ‘Striated Crinoid’ sold for £16,800, beating the previous record for one of her pieces of £7,800. Meanwhile, a wall piece by Ruth Duckworth doubled its estimate, fetching £18,000. There have been successful female ceramic artists for a long while, but somehow this feels significant because the higher up the food chain you go, the more male-dominated the field becomes. With the exception of Lucie Rie, the majority of the dominant figures in studio pottery are men: from Bernard Leach through to Michael Cardew, and more recent artists such as Edmund de Waal and Grayson Perry. Even in the popular TV show The Great Pottery Throwdown, the acknowledged ‘breakout’ star is the tearful Keith Brymer Jones. He has become the fixed point around which female judges – Kate Malone and Sue Pryke – as well as presenters, Sara Cox and Melanie Sykes, have rotated.

Ruth Duckworth, ‘Wall Piece’, 1979

COURTESY: MAAK

However, perhaps Odundo’s ascension into the top ranks of living potters marks a paradigm shift. According to Varrall-Jones a younger generation of collector is looking for a different kind of pot. “I think there’s a return to liking a soft femininity in work,” she explains. “More delicate pieces are drawing new people who hadn’t looked at these kinds of works before.” She cites the likes of Jacqueline Poncelet and Ursula Morley-Price as artists whose prices have risen in recent times, adding that the brown pot is currently struggling to find an audience. “The Leach tradition is not really in favour massively in terms of the market. The great pieces will still fetch great prices but, overall, it’s not what’s in fashion at the moment.”

Magdelene Odundo

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: © Ben Boswell

An early Odundo pot features in a new show at Oxford Ceramics Gallery: Pioneering Women. The exhibition features work from three generations of artists, starting with Viennese-born Lucie Rie (naturally enough) and ending with the Japanese artist Akiko Hirai. In between, there are pieces from the likes of Danish ceramists Bodil Manz and Inger Rokkjaer, the Nigerian artist Ladi Kwali, as well as Alison Britton and Carol McNicoll – who emerged from the Royal College of Art in the 1970s with the aforementioned Poncelet and Elizabeth Fritsch – alongside Jennifer Lee, the winner of the 2017 LOEWE Foundation Craft prize, and Deirdre McLoughlin.

-

Inger Rokkjer, ‘Lidded Jar’, 2006

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Michael Harvey

-

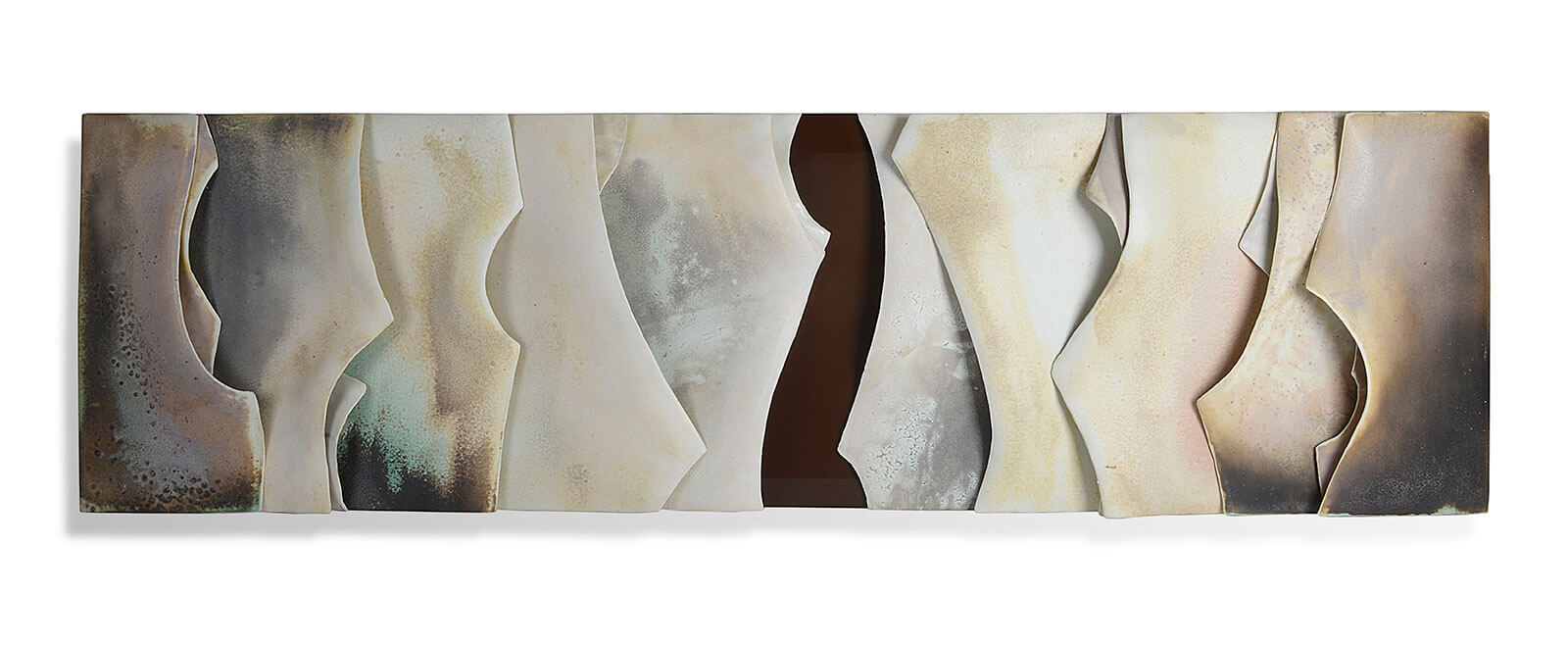

Deirdre McLoughlin, ‘Roll Sister’, 2019

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Michael Harvey

There are a number of threads running through the ten artists on display. There’s the shift from the quiet modernism of Rie to the unabashed post-modernism of Britton and McNicol, for example; the Japanese influence that can be seen in pieces by McLoughlin, Lee and Rie; the fact that a number of the exhibitors have been influential teachers, most notably Rie (again), Britton and Odundo; and, of course, there’s a nod African art too. So how did the co-curators, Amanda Game, and the gallery’s founding director, James Fordham, go about selecting their artists? And why launch an exhibition devoted to women now?

Carol McNicoll

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery

The answer to the second question is that the show was initially planned for the Autumn of 2020, to coincide with Oxford University’s centenary celebrations of the full admission of women to its degree courses, but had to be pushed back because of the virus. “There was quite a festival of the female going on,” confirms Game. That said, the thinking behind the show started back in 2018 when the pair mounted an exhibition, entitled Oxford Pioneers, devoted to the old Oxford Gallery, which closed in 2001. “It was set up by a great female team, including Joan Crossley-Holland, who was a designer for Doulton in the 1930s,” says Fordham. “So this continues the series of pioneers. It felt relevant really. There are dominant male figures of the 100 years of studio pottery, so it’s good to highlight some of the great women that made a big difference.”

Bodil Manz (from left to right): ‘Shadow’, 2019; ‘For Dessau’, 2019; ‘Scandinavia’, 2019

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Michael Harvey

While Rie was an obvious place to start, the pair decided to end with Hirai because they were keen to amplify the Japanese influence. There’s a practical side to this. As Game points out, Japanese ceramics are growing in importance for the gallery. However, as she says: “When we started thinking about twentieth-century Japanese ceramics, the prominent names are all male.” They were keen to redress the balance.

Bodil Manz

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Michael Harris

You sense too that the selection also enabled the curators to have a bit of fun, allowing very different works to rub up against each other – from Rie’s subtle, almost austere vessels to the more obviously flamboyant, slab-built pieces by Britton that quite deliberately set out to explore the boundaries of function. “There is an aspect to exhibition-making where you have the opportunity to juxtapose things that aren’t often juxtaposed,” says Game. “You would tend to see Lucie Rie’s pieces with other work in that tradition. I think it’s often interesting to put things together that aren’t necessarily sitting within their silos or categorisations in art historical terms. It allows you to refresh how you look at the work.”

Lucie Rie, ‘Bronze Vase’, undated

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Michael Harvey

“The selection also enabled the curators to have a bit of fun, allowing very different works to rub up against each other …”

Alison Britton, ‘Outridge’, 2015

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Philip Sayer

“… from Rie’s subtle, almost austere vessels to the more obviously flamboyant, slab-built pieces by Britton”

Did the various artists in the show see themselves as pioneers, blazing a path for others to follow? Alison Britton, for one, isn’t entirely sure. “Not especially,” she tells me. “I think we were enjoying the exploration and relishing the fact we got invited to exhibit internationally. I don’t think you ever want your students to follow directly in your path but you open things out to them and they’ve got to find their own way.” And, besides, she mentions half-joking, clay’s post-modernist moment in the sun was relatively short-lived. “By the time Julian Stair and Edmund de Waal emerged, the scene was all getting cleaned up again with the new white.”

Jennifer Lee, ‘White Bowl’, 2015

COURTESY: Oxford Ceramics Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Michael Harvey

One of the most interesting elements of Pioneering Women is the possibilities it opens. As Game says: “This is a huge subject and this show, clearly, isn’t a comprehensive review. But it’s a hint of something that could be explored further.” It’s very tempting to ask who today’s pioneering female ceramic artists might be. A personal favourite would be Malene Hartmann Rasmussen, whose work is often based around Scandinavian fairy tales and contains a cartoon-like quality that sometimes belies its technical brilliance. Lena Peters is another ceramic artist who has eschewed the pot in favour of figurative work – often part human, part animal – that comes drenched in narrative. Meanwhile, Claire Curneen’s pieces, made from porcelain, terracotta and black stoneware with dribbles of glaze and hints of gold, are full of (often quite disturbing) Catholic imagery.

Malene Hartmann Rasmusse, ‘Fantasma [Ghost]’, 2019

COURTESY: Malene Hartmann Rasmusse

And any list of current pioneers would surely have to include Phoebe Cummings. The artist works in raw clay – so unfired and unglazed – for sculptures that are usually site-specific. Inspired by nature (either real or imagined), her pieces are ornate, fragile and, often, decay over time – giving them a wistful dynamism. This is clay as performance art but perhaps most importantly, in her hands, the material becomes extremely beautiful.

Phoebe Cummings, ‘Gutted’, 2021

COURTESY: Sarah Myerscough Gallery

Phoebe was the winner of the British Ceramics Biennial Award in 2011, picked up the Woman’s Hour Craft Prize in 2017 for a fountain entitled ‘Triumph of the Immaterial’, and was a finalist for the Arts Foundation 25th anniversary awards in 2018. At this year’s Collect, the Crafts Council’s annual international art fair for contemporary craft and design that opens in February, she will be showing new work, which her gallerist Sarah Myerscough describes as “small-scale ephemeral studies of natural flora.” Increasingly inspired by literature, Cummings describes the pieces as “quiet thoughts” that are made of clay and then dipped in wax. “The process offers a layer of strength and protection, though the objects remain fragile and may subtly age over time; they demand care and this act of commitment is significant,” she explains.

Phoebe Cummings, ‘Triumph of the Immaterial’, 2017

COURTESY: V&A / PHOTOGRAPH: Sylvain Deleu

According to Marijke Varrall-Jones, one of the reasons that the work of female potters are beginning to fetch increasingly large prices at auction is that their pieces tend to be incredibly delicate. Because they’re easily damaged or destroyed, fewer remain in pristine condition and, therefore, their value inflates. That being the case it looks as though Cummings could be onto something with her new collection. Time will undoubtedly tell.

Phoebe Cummings in her studio

COURTESY: Phoebe Cummings / PHOTOGRAPH: Alun Callender

Pioneering Women exhibition at Oxford Ceramics Gallery.